Known for staging work that’s as inventive as it is intimate, the Southwark Playhouse continues to make space for stories that matter. With Alex Urwin’s Brixton Calling tucked away in The Little, another production joins that legacy. The story? Simon Parkes buys the Brixton Academy for £1 and turns it into one of the best live music venues in London – the perfect premise for an exciting new show.

Based on Simon Parkes’ bestselling memoir Live at the Brixton Academy, Brixton Calling is a poignant one-act two-hander that charts Parkes’ journey: from a Thalidomide baby in Lincolnshire to the man who bought the Academy for a singular Great British pound. Memoir is a notoriously difficult form to stage. It’s not merely the challenge of distilling a life into 100 minutes, and it is not simply telling a story, but remembering how the story felt. Adding to this complexity is the notion that this is not Parkes’ own adaptation, but the work of writer Alex Urwin. Complexity aside, what emerges is a production that holds both the fact and the feeling, tethered by its humour, heart, and theatrical ingenuity.

Transforming the intimate space of The Little into the lived-in world of the Brixton Academy was never going to be easy, but Nik Corrall’s set design makes an admirable attempt. The stage is framed by scaffolding, clad in concert trappings: old gig posters, glowing graffiti, and a hanging scaffolding circle that cleverly nods to the venue’s famous rotunda. This design immediately situates us in the space, while still allowing the freedom to move through both time and space. The aesthetic is tactile and textured: the grime of the ‘80s is present in the grungy spray-painted walls, and metal structures. It’s impressive, and even more so given how naturally the set shifts – one moment Brixton, the next Lincolnshire, then back again. Yet, the show’s immersive features feel constrained by the physical spatial limits of the stage. There are inventive attempts to pull the audience in: performers using the aisles, handing out flyers, engaging us directly—but there’s a palpable yearning for a deeper transformation of the venue. Brixton Calling feels like a show desperate to spill beyond its proscenium; it doesn’t quite, but it’s not for lack of trying.

Bronagh Lagan’s direction is where the production stands utterly distinct. Two-handers are always a directorial challenge: they require perfect pace, and masterful precision. This production demands its cast embody dozens of characters between them, often within the same breath. One scene in particular stood out on this front – Parkes, alone in a pub, negotiating with three men to buy the venue for £1. The entire conversation is performed by Max Runham as Parkes, flitting between voices, accents, and postures to bring each party to life. Somehow, it’s not only coherent but astonishingly captivating. Lagan knows how to stage momentum, but just as crucially, she knows when to stop. The set may be versatile, but it’s her use of total simplicity that elevates the piece, utilising the sole prop of a box and wire. This becomes at once a memory of fishing, a bicycle, a bank desk and pen, and a feature of the stage at the Academy. These are creative decisions rooted in trust—trust in the performers, in the audience, and in the strength of the story.

That strength also lies in Urwin’s script. Brixton Calling isn’t just a rags-to-riches (or riches-to-riches?) tale. It’s a story of race, class, disability, community, protest, and music. There’s humour here, and plenty of it, but also so much pain. Navigating these tonal shifts is no small challenge, but Urwin makes it look easy. One moment we’re laughing at Parkes dubbing the Academy “the biggest hotbox in London”, the next we’re still, breath held, during a monologue detailing racist microaggressions faced by Parkes’ collaborator Johnny Lawes. That particular moment, delivered with searing intensity, lingers. It’s not just a historical account of the Brixton Riots. It’s a lived memory—raw, specific, and unflinching. Just minutes later, we’re meeting Miss Tuna Turner, a drag queen whose presence has the audience roaring. The oscillation between joy and pain, friendship and brutality, and success and injustice, is handled with deft precision.

While the set and script lean beautifully into simplicity, the lighting design – by Derek Anderson – sometimes overreaches. When it works, it really works: the scene in which Parkes is thrown out of Blondie’s gig, lit from above to give the illusion of him floating, is visually stunning. The bomb scare sequence, with the stark white flash, is similarly effective. But elsewhere, the lighting lacks discipline. A persistent yellow-orange haze bathes much of the show, and while it aligns aesthetically with the stunning promotional materials, it often leaves the actors’ faces in shadow. Emotional beats thus get lost in the murk. As present through the set and the direction, lighting would benefit from restraint, with creative simplicity allowing the complexity of the performance demands to shine.

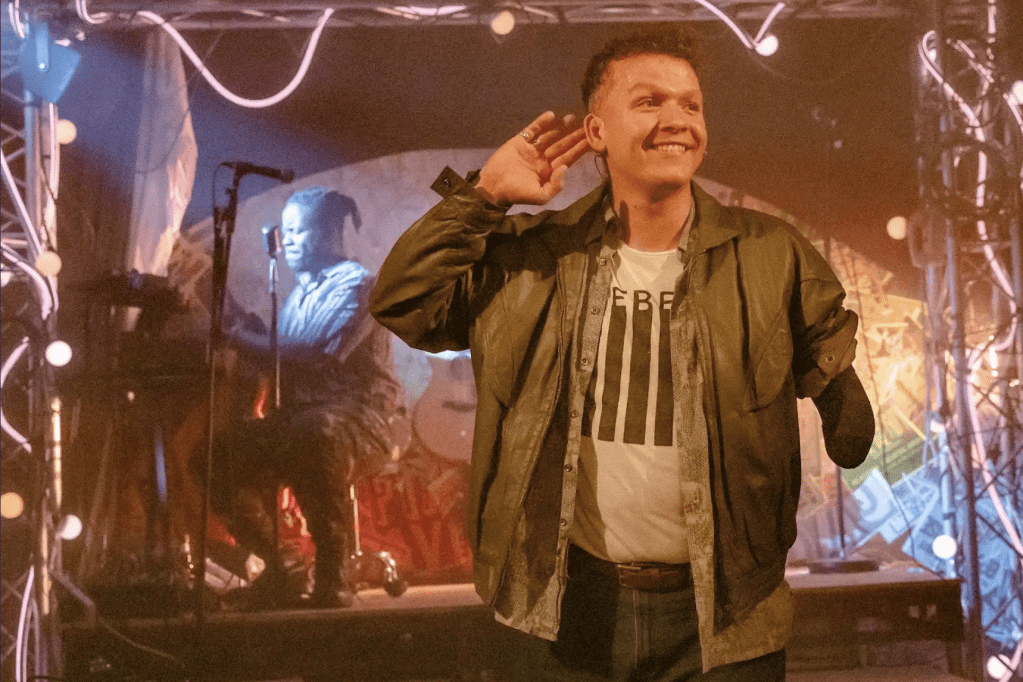

On that, the electricity of the performances is undeniable. Max Runham, as Simon Parkes, gives a performance of astonishing breadth. Rarely offstage, he shoulders the weight of the narrative with a clarity and charm that never once wavers; his stamina is remarkable. His Parkes is a contradiction—financially privileged yet constantly fighting, disabled but endlessly resilient, sharply observant yet frequently bewildered. Runham plays the role not as a self-absorbed entrepreneur, but as a man who kept showing up – it is this humanising of Parkes that makes it compelling. The emotional arc—particularly Parkes’ navigation of family dysfunction and physical adversity—is delivered with humour and heart.

Tendai Humphrey Sitima, meanwhile, might be one of the most versatile performers on stage right now. He transitions between roles with dizzying ease: posh schoolboys, brutal coppers, the stoic Academy security, and even a drag queen. Alongside these, his take on Johnny Lawes is emotive, raw, and so deeply human; it is beautiful. Each character arrives fully realised, fully embodied, fully alive. There’s never a wink to the audience, and never a moment where it feels like a sketch show. It’s fully integrated storytelling – and it’s thrilling.

The chemistry between Runham and Sitima is masterful. Their dynamic is elastic and alive – you believe in this partnership. So much so, that when Runham as Parkes shared that they made a 2.5 million percent return on the original £1 investment, the audience erupted into applause: proof that everyone in the theatre found their partnership just as compelling as I did. It wasn’t necessarily borne from awe of the profit, but a shared emotional investment in the story of Simon Parkes himself, and a guttural belief in the portrayals of Sitima and Runham.

Brixton Calling succeeds in all the hardest places. It balances memoir with meaning, memory with immediacy. It’s political but never preachy, historical but never dusty, and funny without ever undermining its seriousness. It is a genuine triumph, and one I am excited to see grow.

Brixton Calling is running at the Southwark Playhouse Borough until August 16th, 2025. Buy your tickets here.

Image credit – Danny Kaan

Leave a comment